Blind Men and the Elephant

Blind Men and the Elephant was composed and performed as part of my master's thesis. The score consists of a series of repeating modules, each one measure in length, and read on a computer screen in front of the performer. The instrumentation is variable but requires two polyphonic instruments and one monophonic instrument in a low register. In some modules, performers are given a set of pitches and a rhythmic phrase, and the pitches can be played in any order. In others, pitches are given in a certain order but the rhythm can be improvised. And in others, the modules are through-composed.

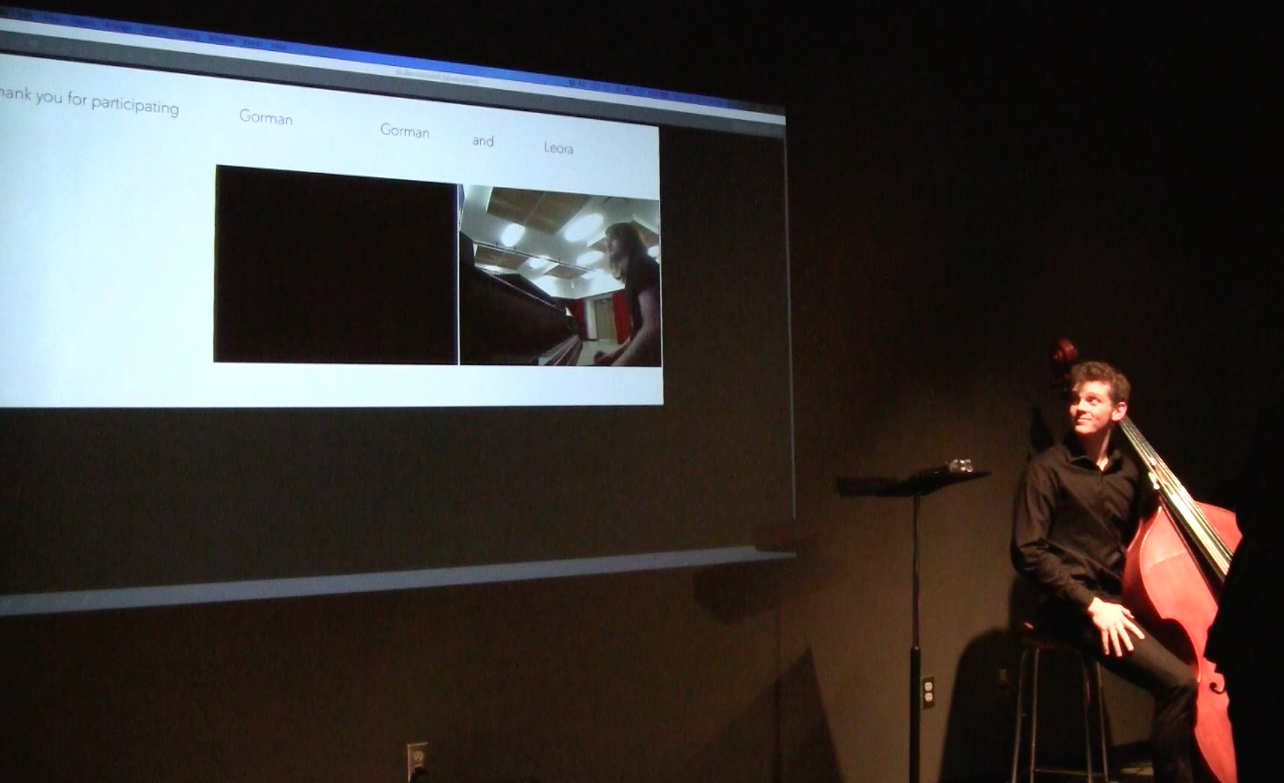

The piece utilizes network music’s unique affordances by involving audience participation via Twitter. For each module, there is a legato version, a staccato version, a version with an accent pattern, and a version that changes dynamic. Audience members are encouraged to post tweets during the performance that include one of the terms, “legato”, “staccato”, “accent”, or “dynamic”, and tag the username “@telephantmusic”. At numerous random points in time, the piece’s software scrapes Twitter for these tweets and changes the performers’ score to reflect the audience members’ suggestions.

Program Notes:

Blind Men and the Elephant takes its title and inspiration from an ancient story originating in southern Asia. Having suffused many religious traditions over hundreds of years, the story has come to be a valuable analogy for the manifold nature of truth.

In the story, a group of blind men (or “men in the dark”) set out to understand the form of an elephant. One man touches the leg and determines an elephant is like a pillar, one touches the trunk and determines an elephant is like a rope, and one touches the ear and determines an elephant is like a fan. The conclusion of the story is different among the many versions told over time. In some, the men argue violently over who is right or wrong. In others, a sighted (omnipotent) person reveals that they are all partially right. And in other versions the men come together to communicate and arrive at an agreement. Thus, the story itself can be understood from different viewpoints, making it a clear example of self-reference.

The notional interactions of perspectivism, pluralism, and self-reference are not only compositional inspiration for the piece, they are also physically manifested in the process of its performance. At each performance space (or "node") sonic events unfold in different orders due to latency in the speed of data transmission. The piece itself, like all performed music, is a single activity - a sequence of sonic events spanning a length of time. However, each listener (and performer), depending on their location, hears these events unfolding in a different order. The act of performance is singular, but the experience of the performance is manifold.

The beauty in this, for me, lies in the fact that a reconciliation of all perspectives (omnipresence or agreement) is physically impossible. There is no ultimate listening location, no one “true” form of the performance. A deeper reading of the story of the blind men and the elephant also yields this conclusion - while we may conceive of a “true” elephant form, we do so individually and we require others’ perspectives to inform that conception.

Every participant contributes to the piece; as both listener and performer, the music is shaped by momentary decisions and by a body’s physical location. Therefore, reconciliation among all participants’ perspectives is found by embracing disparity and focusing on the shared process of making music together.

Instructions:

Any time during the course of this performance feel free to send a tweet that uses one of the following terms: legato, staccato, accent, or dynamic. Use only one term at a time, but tweet as many times as you'd like. Include the username @TelephantMusic and your input will be used in the realization of the piece. (example: Staccato @TelephantMusic)